ResearchI am interested in the 'night side' of human experience, in the role that dreams, ghosts, and hallucinations play in our everyday lives and histories. My key research questions are: how do people deal with disappearance and missing, or ghosted, people? What were the particular histories that led us to lose our belief in the authority of dreams and ghosts? And, how does the past stick around and haunt the present through landscapes, memories, bodies, and objects? Although trained as a cultural historian, I believe that uncovering the 'spectral' origins of western modernity demands a thoroughly interdisciplinary approach that uses concepts and arguments from human geography, environmental humanities, and medical humanities. I have applied these interests and approaches in several research projects.

|

Spectres of the Self |

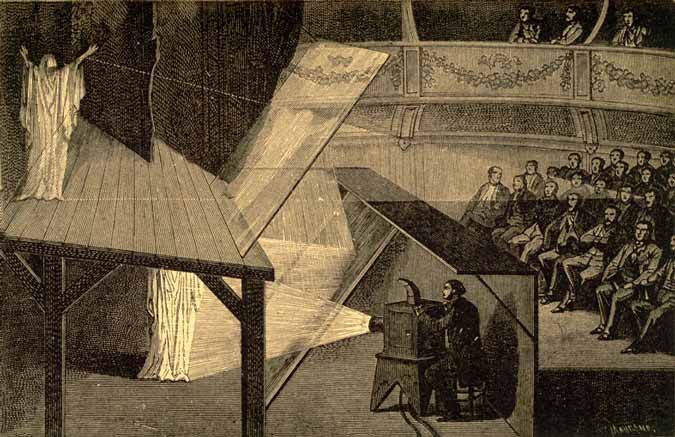

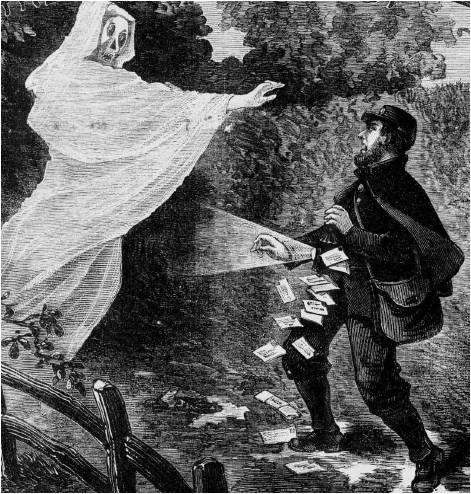

This project emerged from my PhD research at University College Dublin. My core question was, how has the idea of ghost-seeing changed over time and why do we now associate ghosts with psychological disturbance? In my research I argued that since the Enlightenment in Europe, ghosts came to be internalised as 'spectres of the self' by cultural elites, who began to think of supernatural apparitions as self-generated projections of the mind. As seemingly sane, rational, and intellectual people continued to see ghosts, thinkers in Britain especially had to devise new scientific concepts to prove that ghosts were seen, but that these visions were hallucinations. In my book Spectres of the Self: Thinking about Ghosts and Ghost-seeing in England, 1750-1920 (2010) I argued that the Society for Psychical Research, with their concept of telepathy, reflected the tension between scientific naturalism and data which suggested the existence of ghosts. Reviews of the book can be found here.

|

The Ghostly Arctic |

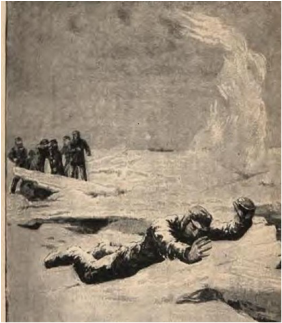

People from western cultures who visit the Arctic enter places that have been traditionally imagined as being 'magical' or 'unearthly'. This strangeness particularly fascinated audiences in nineteenth-century Britain when the idea of the heroic polar explorer voyaging through unmapped zones reached its zenith. Yet scholars have tended to downplay the recurring senses of ghostliness and dreaminess that run through narratives of polar exploration. The Ghostly Arctic was a project I undertook while I was a Marie Curie Fellow at Maynooth University and the Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge (2010-13). In contrast to oft-told tales of deering-do and disaster, I wanted to reveal the hidden stories of dreaming and haunted explorers, of rescue balloons and visits to Inuit shamans, and of the entranced female clairvoyants who travelled to the Arctic in search of Sir John Franklin's lost expedition. My revisionist historical account - The Spectral Arctic: A History of Dreams and Ghosts in Polar Exploration (UCL Press, 2018) - allows us to make sense of current cultural and political concerns in the Canadian Arctic about the disappearance and reappearance of the Franklin expedition.

|

The History of Irish Science |

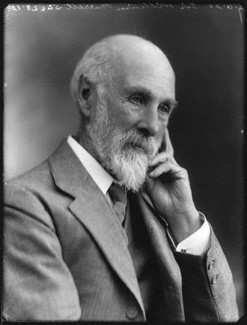

In 2009 I undertook a research project at University College Dublin's Irish Virtual Research Library and Archive on the history of the Royal College of Science for Ireland (1867-1926). The RCScI was an innovative centre for the training of generations of geologists, physicists, and engineers and formed the basis of scientific education in twentieth-century Ireland. However, it suffered from low student enrollment and a lack of engagement from middle class nationalists in Dublin and this resulted in its amalgamation with UCD in 1926. Its grand headquarters on Merrion Street, designed by Sir Aston Webb, are now Government Buildings. My research entailed work in the archives and library of the RCScI which UCD inherited; contextualising the impact of the RCScI in the history of higher education in Ireland; and a case study of Sir William Fletcher Barrett, an English physicist of international renown who lectured and lived in Dublin for some time. Barrett was interesting as a Home Ruler and supporter of suffragism, but he was also a leading light in the Society for Psychical Research and many of his best-known writings on telepathy, spiritualism, and the divining rod emerged from his time in Dublin. A report on this research project can be found here.

|

The Criminal Corpse in Pieces |

From 2013 to 2015 I was a member of an interdisciplinary team at the University of Leicester which was funded by the Wellcome Trust. Our project - 'Harnessing the Power of the Criminal Corpse' - looked at what happened to criminals after they were executed - their journeys through postmortem legal punishment, medical anatomy, relic-hunting, gibbeting, museum display, and magical dismemberment. This led us to several important conclusions: there were many forms and timelines of death in capital punishment, and legal death by hanging was only one form; criminal bodies were believed to contain an aura, or glamour. Those who hovered around the body after death included medical students who wanted to investigate the effects of strangulation, and collectors, witches, or thieves who wanted criminal body parts as mementos or magical objects. In my research I have looked at the fascination people have with fragmenting and owning pieces of criminal corpses. I focused in particular on the case of William Corder who was hung, anatomised, galvanised, broken up, and displayed after his execution in 1828. Following this I turned to an examination of the 'hand of glory' - an ancient folk-belief that possessing the severed hand of a hanged man could assist criminals in housebreaking and offer the owner access to hidden treasures. This belief migrated from folklore and social history into gothic literature throughout Europe in the nineteenth century. This research offers insight into the postmortem lives of executed criminals but also shows how current unethical and violent body or organ 'trades' have a long history.

|